The tonsils and tonsillectomy

Introducing Coblation® Intracapsular Tonsillectomy

What are the tonsils?

The tonsils are lumps of soft tissue which lie on either side of the back of the throat, which rest on a bed of muscle and blood vessels. They are part of the immune system, just like the adenoids. The tonsils act like a sentry point or CCTV for the throat, picking up virus and bacteria particles which are breathed in or swallowed, and relaying these to the immune system. The adenoids do the same for the nose. To help with this role, the surfaces of the tonsils are pitted with a number of little recesses, also called tonsil crypts. These increase the surface area of the tonsils, relaying more viruses and bacteria to the immune system, but they can also become clogged up with bacteria and food particles which can lead to problems.

Enlarged tonsils

The tonsils, like the adenoids, tend to be very small in babies, but grow significantly in toddlers and pre-school children. They are usually smaller by adolescence and adulthood, but may sometimes remain large.

In reality, the tonsils may need to be removed for a number of reasons, sometimes even in very young children. We believe that the tonsils are important in the developing immune system in infants, but they may have less benefit after about two or three years of age. Although there has not been a lot of evidence to support these assumptions in the past, a very recent study (click here to view) has suggested that removal of the tonsils (and adenoids) may be associated with higher chances of other medical issues in the future, such as allergies, asthma and chest infections. So tonsil and adenoid surgery should be considered only if they are causing significant problems and if there are no obvious alternatives to surgery.

What problems can the tonsils cause?

The main problems requiring treatment are obstruction to breathing and sore throats (tonsillitis). There are also some less common ways in which the tonsils cause problems.

Breathing problems

The tonsils may be quite prominent compared to the size of the throat, particularly in young children who have relatively small throats and relatively large tonsils. Tonsils may therefore create difficulties with breathing by physically obstructing the airway, particularly at night. When we sleep, our muscle tone reduces and we become floppy. The muscles in the soft tissues around the throat (soft palate, and tongue base) also become floppy, causing the airway of the throat to collapse a little. If the tonsils are also large, the airway becomes even more cramped and restricted, leading to snoring and even obstructive sleep apnoea.

Sore throats and tonsillitis

Sore throats are very common, particularly among children. These are most often caused by cold viruses, but bacteria are also sometimes involved (particularly in more severe cases, with high fever). The throat becomes generally red and inflamed. During these spells, the tonsils may also look red and inflamed, just like the rest of the throat, particularly in young children. This does not necessarily mean tonsillitis. If the infection becomes worse, blebs of pus may appear on the surface of the tonsils, and we call this tonsillitis. This may result in severe pain, difficulties swallowing and high fever. Other complications can also sometimes arise, including an abscess around the tonsil (a quinsy) and fever-related problems (such as febrile convulsions). A form of tonsillitis may also occur in glandular fever.

Peri-tonsillar abscess (quinsy)

Occasionally, tonsillitis may lead to severe inflammation and soft tissue swelling around the tonsil. A collection of pus may form, as the body tries to fight off the infection. This is called a peri-tonsillar abscess, or quinsy. This scenario is more common in adolescents and adults than in young children.

A quinsy will often need to be drained to release the pus. This can be done through the mouth in the clinic, with a local anaesthetic. High dose antibiotic treatment will usually allow things to settle within a day or two. Repeated quinsy is another reason why the tonsils might require treatment.

Glandular fever

This is relatively common in adolescents and young adults, and is caused by a virus transmitted in saliva (Epstein-Barr virus, or EBV). A variety of the body’s systems may be involved. Tonsillitis is common, usually with a white film coating the tonsils, rather than the smaller pustules in typical tonsillitis. The lymph glands of the neck will also often flare up. The liver and spleen may also become inflamed and enlarged. The GP or ENT doctor should therefore examine the abdomen if glandular fever is suspected, and contact sports should be avoided for at least six weeks, in case a blow to the abdomen causes damage to the liver or spleen. A simple blood test will often confirm the diagnosis, but is not always reliable.

Otherwise, treatment is generally supportive: plenty of rest, simple painkillers, fluid and food. Alcohol should be avoided. Antibiotics are not usually helpful; in any case, avoid amoxicillin (on its own or in other preparations), as this can cause a nasty rash. Admission to hospital is sometimes necessary.

Debris in the tonsils (“tonsil stones”) and bad breath

The little pits in the tonsils may accumulate bacteria and food particles, which some people find uncomfortable or smelly. Careful tooth brushing and use of mouthwashes will often help, so that removal of the tonsils for this reason alone is not usually recommended.

Feeding difficulties and drooling

Large tonsils at the back of the throat may occasionally make swallowing difficult for children, and may also make drooling more likely if the saliva is hard to swallow. Again, these problems are not usually bad enough on their own to justify removal of the tonsils.

Asymmetrical tonsils and growths within the tonsils

Unequal-looking tonsils are quite common. In reality, the apparent asymmetry usually results from one of the tonsils swinging out more than the other when the throat is examined.

Very rarely, one or both tonsils may become enlarged as a result of a growth, either arising in the tonsil(s) or spreading from elsewhere. These are exceptionally rare in children. If there is any doubt, then the tonsils may be removed and sent for analysis.

Diagnosing tonsil problems

The most useful information comes from the patient or parents and carers, and the lines of questioning will depend on the types of problems encountered.

For infections and tonsillitis, it is important to be clear about the episodes. Treatment for tonsillitis by removal of the tonsils may be very painful and carries significant risks- it is therefore not recommended for milder cases of sore throat, where watchful waiting may be better.

Were there attacks of true tonsillitis, with big, red, pus-covered tonsils, severe pain and high fevers (confirmed by a GP) or just prominent red tonsils in a generally sore throat?

How frequent were the attacks, over what period, and are they any more or less frequent now?

How much were everyday activities affected (including feeding, school, play, work etc)?

How much time has been missed from school or work?

Have there been any other complications?

Are immunisations up to date, and are there any other major health problems?

Children with mainly obstructive symptoms and breathing problems are likely to have some of the symptoms detailed in the snoring and obstructive sleep apnoea section.

Treatment for tonsillitis

The Scottish SIGN guidelines for tonsillectomy provide a useful framework for diagnosing and treating tonsillitis. The pocket guide can be viewed here. GPs and ENT specialists in the UK will generally refer to these in decision-making. Milder cases can be managed by observation or medical treatment, but the evidence generally supports removal of the tonsils for repeated severe tonsillitis occurring three times per year for three years, five times a year for two years or seven times in one year.

Although rarely encountered, any patient with major breathing or swallowing problems from a sore throat should be seen urgently in hospital by an ENT specialist, and not examined out of hospital in case the problems are made worse.

Many attacks of sore throats and tonsillitis are viral, so that antibiotics may not help at all. For each attack, simple supportive measures should be used in all cases, including plenty of fluids, rest, simple pain relief (paracetamol and ibuprofen) and cooling measures during high fevers.

The SIGN guidelines also include the Centor score for tonsillitis, which may be helpful (but not entirely reliable) in predicting whether the infection is bacterial and if antibiotics are required:

This gives one point each for:

Pus on the tonsils

Tender lymph glands in the neck

History of fever

No cough

The likelihood of a Streptococcus bacterial infection increases with an increasing score out of 4. The chance is 25-86% with a score of 4/4 and 2-23% with a score of 1/4. Bacterial infection is more likely in children aged 5-15.

For repeated episodes of tonsillitis, several options are available

The infections can be treated each time they occur, as above, hoping that the attacks may reduce with time (treatment + watchful waiting).

Some specialists may try a low dose preventative course of antibiotics, to be used for a number of weeks at a time. Examples include amoxicillin, co-amoxiclav (Augmentin) and azithromycin.

Tonsil removal (tonsillectomy) may be warranted if attacks are severe and frequent, and if there have been any significant complications.

Treatment for snoring and sleep apnoea

Depending on the age of the patient and relative size of the tonsils, tonsillectomy (often combined with adenoidectomy) may be very helpful by increasing the space in the airway. The relative merits of surgery are covered in the snoring and sleep apnoea section.

Treatment for other tonsil problems

Other tonsil-related problems should be assessed and treated on an individual basis. There may be circumstances, for example, where tonsillectomy is reasonable. Above all, the risks and benefits of surgery or medical treatment should be weighed up against simply watching and waiting.

Tonsillectomy

How are the tonsils removed?

There are a number of ways in which the tonsils may be removed. In simple terms, this can be done either by simple “cold steel” dissection, with scissors and other simple implements, or using electrical instruments. Different ENT surgeons will prefer particular methods.

I tend to use one of two electrical methods:

1. Dissection tonsillectomy.

This is a very commonly used method in the UK. A pair of electrical forceps or a metal dissector are used to get in between the tonsil and the underlying muscle, cauterising or tying off blood vessels one by one. It can be thought of like "shelling out a grape": removing the whole tonsil each side and leaving behind exposed muscle and cauterised blood vessels. The muscle will heal over within 7-10 days or so. This is a well-established technique, but carries significant risks of pain and bleeding after surgery.

2. Coblation® intracapsular tonsillectomy (tonsillotomy).

This uses an electric probe which has a suction channel and drips out salty water (saline). The electric current excites the molecules in the saline fluid, and then the energy from these excited molecules causes the proteins in the tonsil tissue to break down, like blanching an egg white. This all occurs at 40-60°C, with very little heating effect to the surrounding tissues compared to other electrical techniques.

Coblation® (or radiofrequency ablation) has been used around the world for a number of years to remove tonsils in the traditional manner- “shelling out a grape”, and leaving behind exposed muscle and cauterised vessels. Some surgeons believe that this instrument, used in this traditional way, is better than others, but the evidence is mixed. Apart from possible differences in pain and recovery time after surgery, we also have to factor in other risks, such as bleeding. For tonsil removal in the traditional, “shelling out” way, many techniques seem to give similar results.

Pain and bleeding are always major concerns after traditional tonsil removal. Exposed muscle is full of nerves and is therefore often painful while it heals over (taking 7-10 days). The tonsils lie on a bed of large blood vessels. These are cauterised or tied off as the tonsils are shelled out, but can bleed again at any time within about two weeks after surgery. Such bleeds may be heavy, and sometimes require another operation so that the bleeding can be stopped. This is a particular concern in little children who have small total blood volumes.

For these reasons, ENT surgeons in children’s hospitals have thought about alternative ways to remove the tonsils. Instead of shelling out the tonsils like grapes, and therefore exposing the painful muscle and bases of the blood vessels, some surgeons have tried debulking the tonsils, using a variety of methods. The tonsil tissue is nibbled or dissolved away, leaving a thin inner layer behind to protect the underlying muscle and blood vessels. This can be thought of like removing most of a grape but leaving behind small amount of grape flesh and the inner layer of grape skin intact. This technique is all done from inside the tonsil lining (the “capsule”), and so is called “intra-capsular”. This form of surgery is also sometimes known as "tonsillotomy".

In the USA, for instance, these techniques have been used for a number of years, mainly for children with snoring and sleep apnoea, but also sometimes for tonsillitis, with promising results. In theory, because the sensitive muscle is not exposed and since the tonsils do not contain nerves, pain should be less after surgery. And the bases of the blood vessels are also not exposed, therefore hopefully reducing three risks of bleeding. The main method used in the USA has been a microdebrider- this nibbles the tonsil tissue away like a tiny hand blender, although bleeding points may then need to be cauterised using hot electrical current (as above).

Experience at Evelina London Children's Hospital

Together with colleagues at Evelina London Children’s Hospital, I have led a study using the Coblation® method to perform this type of intracapsular tonsillectomy, particularly in young children where quick recovery and minimum pain and bleeding are so important. This is the first and largest prospective study of its type in the UK. Results from the first 100 cases were published: please click here to download the article. I have also recently published data from my first 500 cases, available here, and our latest series looked at results in over 1200 cases.

So far, in over 2500 paediatric and 250 adult cases, I have seen excellent results in terms of relief from symptoms of snoring and sleep apnoea, limited pain and painkiller requirements after surgery, quick recovery and no cases of delayed discharge or readmission with pain. Bleeding after surgery has been rare: about 1 in 300 children and 1 in 75 to 1 in 100 adults come back to hospital following a small amount of bleeding at home which settled on its own. Parents' satisfaction has typically been excellent.

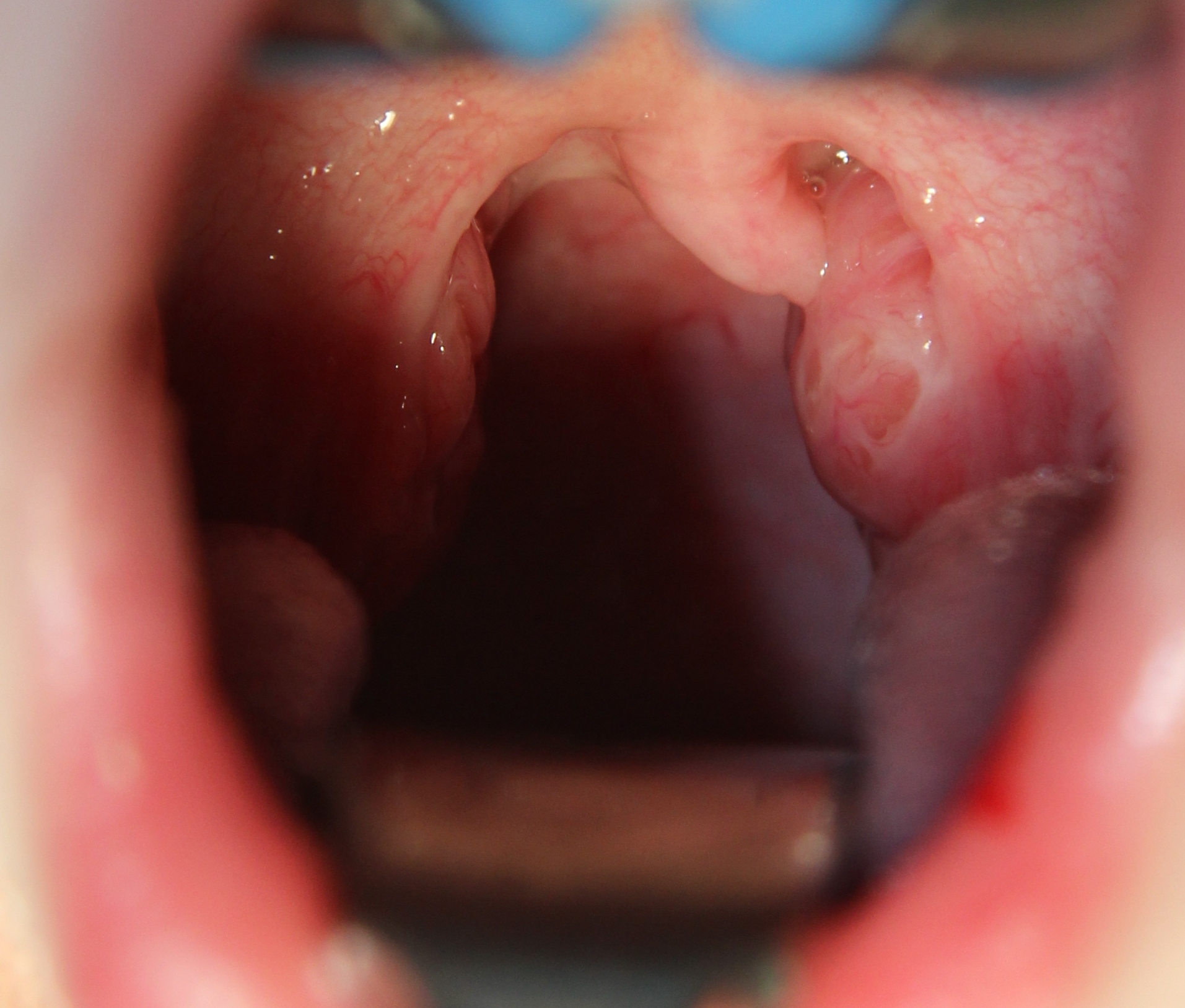

Large tonsils before tonsillectomy. These lie either side of the uvula- the soft tissue which dangles down at the back of the throat (Daniel Tweedie).

The appearance immediately after Coblation intracapsular tonsillectomy. The muscles of the throat are intact, and there is no obvious tonsil tissue to see (Daniel Tweedie).

What are the risks of tonsillectomy?

My experience of Coblation® intracapsular tonsillectomy in over 2500 paediatric and 250 adult cases suggests a very low rate of complications- I have seen no cases of major bleeding which required intervention (return to the operating room) in my series, or severe pain requiring delayed discharge or readmission to hospital, with a generally rapid return to normal activities. For children, the average time to go back to school or nursery is 6 days. For adults, return to work may be possible within one week, but I would suggest up to two weeks off before reliably being able to return to work.

Nonetheless, it is important for patients and parents to be aware of the typical risks of traditional tonsil surgery.

UK National Audit

As with most types of surgery, tonsillectomy carries some important risks. The UK National Prospective Tonsillectomy Audit 2005 looked at the main risks in detail, and provides a guide to the likely chances of problems after tonsil surgery, although the actual figures will vary slightly between techniques and by chance in individual cases. The data looked at various ways of removing the tonsils in the traditional, "shelling out a grape" manner, rather than newer debulking techniques. The document can be downloaded here.

Getting it Right First Time

More recently, NHS Improvement carried out Getting it Right First Time reviews across major surgical specialities, including ENT.

The ENT report was published in November 2019 and can be downloaded here: it covered 48747 tonsillectomies in children and 22889 tonsillectomies in adults across 126 hospitals in England, looking at rates of readmission to hospital with bleeding and pain, for example.

This highlighted major differences between hospitals in terms of readmission rates after tonsil surgery, ranging from 3.7%-18.6% in children and 9.2%-31.2% in adults, much higher than the figures quoted from the previous national audit.

Results at Evelina London Children’s Hospital

The Getting it Right First Time document reported that our unit had the very lowest readmission rates after tonsillectomy in children of any large centres in the country. Readmission rates with all methods of tonsil surgery were 3.7% (1.5% with bleeding) but in the two thirds of all our patients who underwent Coblation intracapsular tonsillectomy, the readmission rate was 0.4% (one in 250 patients).

This is a graph taken from the Getting it Right First Time report for ENT (November 2019). The results for all 126 units in England are plotted, highlighting the overall readmission rate for the Evelina (dark blue) and separately the Evelina’s readmission rate for Coblation intracapsular tonsillectomy (in pink). The best results (lowest readmission rates) are found lower down on the graph, and data from larger units are plotted towards the right.

Bleeding

So far, the readmission rate for bleeding in my series is around 1 in 300 children and around 1 in 75 to 1 in 100 adults. All of these cases were managed conservatively, with the bleeding stopping on its own, with no need for a return to the operating room in any cases. The data from other centres worldwide supports lower risks of bleeding than with traditional surgery.

But patients and parents should be aware that bleeding after tonsil surgery can be heavy. Any patient with blood in the mouth after tonsil surgery should be taken to A+E immediately for ENT assessment. You may need to dial 999 for an ambulance. A high proportion of bleeds may settle without another operation, but in rare cases, some (particularly young children) will need a further general anaesthetic for a small operation so that the bleeding can be stopped. In very rare cases, a blood transfusion may be needed.

Pain

Traditional tonsillectomy is painful in many cases, sometimes getting worse a few days after surgery. The pain affects mainly the throat, but can also sometimes affect the ears: the same nerves supply both areas. Although some children might manage with paracetamol and ibuprofen, others (and particularly older children and adults) will often require something stronger, such as codeine-based medicine or a more powerful anti-inflammatory such as diclofenac.

It is essential that pain is kept under control. If patients struggle to eat and drink as a result of pain, they may have a higher chance of bleeding. The best way to avoid this is to give good doses of painkillers regularly, even if the patient seems well. Pain is then less likely to appear unexpectedly- it is harder to treat than to prevent in the first place.

Our experience so far suggests less pain with the Coblation intracapsular tonsillectomy technique, but advice regarding regular painkillers remains the same: paracetamol (Calpol) and ibuprofen (Nurofen) should be used regularly for up to a week after surgery, and possibly on an "as required" basis for a further week.

Damage to the teeth, lips and gums

This occurs rarely during tonsillectomy, because of the metal instruments which are inserted into the mouth. Please let your surgeon and anaesthetist know if your child has any loose, decayed or chipped teeth before surgery.

Jaw joint discomfort or clicking

This sometimes happens because the mouth is stretched open during the operation. The problem will usually settle with time.

Persistent or recurrent symptoms

Despite tonsil removal, some patients may still have some of the problems they had before, such as sore throats, snoring and so on: their symptoms persist. In other cases, things may improve for a while, and then get worse again: the symptoms recur.

In the patients who have undergone intracapsular tonsillectomy in my series, now well over 2500 children and 250 adults in 13 years of practice, about one in forty to one in fifty (2-2.5%) have had persistent symptoms as a result of tonsil regrowth, requiring repeated surgery. These include mostly very young children (aged 1-2 at the time of initial surgery) who had a small amount of tonsil regrowth and recurrence of snoring, and a very small number of other children and adults had further tonsillitis. It should be borne in mind that even patients undergoing "traditional" tonsillectomy may also suffer persistent or recurrent symptoms as a result of tonsil tissue which is left behind, and studies comparing the two techniques have not shown a dramatic difference between the two techniques in terms of eliminating symptoms.

The relatively small chance of some persistent problems after surgery should be weighed up against the risk of more serious complications such as severe pain or bleeding.

What about after surgery?

The majority of patients who undergo Coblation intracpasular tonsillectomy can go home on the same day, particularly older children and adults. Young children, those living far away and some with other problems may need to stay in hospital overnight.

The throat may be sore. Please administer painkillers regularly for a week (paracetamol and ibuprofen, both together, four times a day), whether or not the pain is particularly bad. It is worth having syringes ready with the medication for use overnight, when the previous painkillers may wear off in the early hours and children sometimes wake up in discomfort.

The back of the throat will become white and chalky, and may smell unpleasant. This is entirely normal, and does not require antibiotics or other treatments.

It is always sensible to inform schools and employers that patients may need up to two weeks off after tonsil surgery. But in practice, using Coblation intracapsular tonsillectomy, many of my patients and parents report very rapid recovery, allowing return to these activities much more quickly, even within one week.

If pain gets worse, please see your GP or local A+E as soon as possible for some stronger medication. Pain which prevents eating and drinking may make bleeding more likely. Please note that the UK's Medicines and Healthcare Products Regulatory Agency (MHRA) has recently outlawed the use of codeine in all under 12s, and any under 18s with a history of sleep apnoea. Further details are available here. Alternatives include oral morphine solution and dihydrocodeine. In my practice, these have not been required after intracapsular tonsillectomy.

Children and adults should be encouraged to drink as much fluid as possible in the days after surgery: the urine should be pale or colourless, showing that it is nice and dilute and therefore the person is drinking enough.

There is no specific advice about what to eat. Children in particular should be encouraged to eat whatever they like in the days after surgery (within reason), to ensure they receive sufficient calories.

Please avoid swimming for two weeks after surgery, to allow everything to heal and to minimise the risks of bleeding and infection.

You should not fly for about 2-3 weeks after surgery. Other travel within this time should be limited to areas where medical support is easily available.